Vital Inc.

Radical need seeker and market reader cauldron, spiral staircase and fertile field style firm innovating its organizational structures, innovating its management system and innovating its services

2020-03-03

InnoSurvey™ - Basic report

Vital Inc.

Radical need seeker and market reader cauldron, spiral staircase and fertile field style firm innovating its organizational structures, innovating its management system and innovating its services

2020-03-03

InnoSurvey™ - Basic report

1 About this basic Report

2 Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

3 Recommendations

4 The InnoSurvey™ innovation framework

5 A Review of current thinking

5 Reference list

Congratulations, you now hold an

“InnoSurvey™ Basic Report” in you hand!

The InnoSurvey™ Basic Report is automatically generated from your

individual answers to the innovation capability survey.

The report provides a set of evidence based, standard recommendations for improving your innovation capability, based on our innovation capability framework and comparisons (benchmark) with relevant data from our large innovation database.

We hope you will find this report both awakening, interesting and useful.

Innovation 360 Group help companies to sharpen their innovation capability, generate and re-innovate their value propositions as well as speeding up their global goto market projects. We do this by means of research based innovation capability measurement, our global innovation database, evidence based analysis and recommendations on concrete execution plans for increased innovation capability, profit and growth. Our specialities are Innovation capability development and innovative improvements of our clients profit and growth through strategy, business modelling, ideation, prototyping, commercialization and transformation of our clients organization models and their capability to execute and launch with excellence.

The Innovation 360 Group’s founding team has long term experience from working with innovative clients on the international market. As a firm we work primarily with organisations with high ambitions and strong international focus on innovation, profit and growth.

Our mission is to support and strengthen the global innovation capability needed to address humanity’s grand challenges: Food, Energy, Water, Security, Global Health, Education, Environment, Poverty and Space. Our aim is therefore to help 1,000,000+ entrepreneurs, companies, executives and scientists all over the world to become world class innovators through providing our unique innovation measurement tool and database, InnoSurvey™ as a free-to-all digital on-line service complimented with an enterprise tool and consultancy services by our consultants as well as through licensed practitioners all over the globe.

Please note: The InnoSurvey™

Basic Report presents the result of an individual measurement only!

A full corporate innovation capability measurement would require the

“InnoSurvey™ Enterprise Solution”, and is set up with 8-10 external

and internal respondents as well as in-depth interviews and provides a full

fledge innovation capability analysis and insight. The Enterprise Report

contains more specific analysis, a wider set of relevant benchmarks and a

larger set of specific and more precise recommendations, as defined by our

innovation expert consultants. The Enterprise Report therefore provides you

with a ready-to-go strategic starting point for sharpening your Innovation

Capability and thus assuring the future success of your business!

If you are interested in doing an

Enterprise measurement on your company, please feel free to contact us at info@innovation360.se, or visit our web at www.innovation360group.com

for individual contact persons.

Overall, the relevance check, regarding whether the company applies innovation thinking and practice, is 100 %, and indicates how relevant it is to measure the innovation strategy, leadership, capabilities, culture and type of innovation.

Most of the world's 1000 innovation top-spenders can be described as belonging to one of three categories, in accordance with their innovation strategy: need seekers, market readers and technology drivers (Jaruzelski & Dehoff, 2010). These categories are described in more detail in section 5.6 below.

The company's strategy can be described as:

• The organization is driving innovation to gain and maintain a superior profit level.

• The organization is driving innovation in order to grow and/or to strengthen its competitive position.

• The organization has a need-seeker innovation strategy - it actively engages current and potential customers to shape new products, services, and processes, striving to be first to market with those products.

• The organization has a market-reading strategy, meaning that it watches the markets carefully, maintaining a cautious approach, focusing largely on creating value through incremental change.

• The organization uses radical innovation. Radical innovation entail unexpectedly large product or service improvements, or first-of-a-kind technology applications. It could also involve the creation of entirely new markets, technologies or business models.

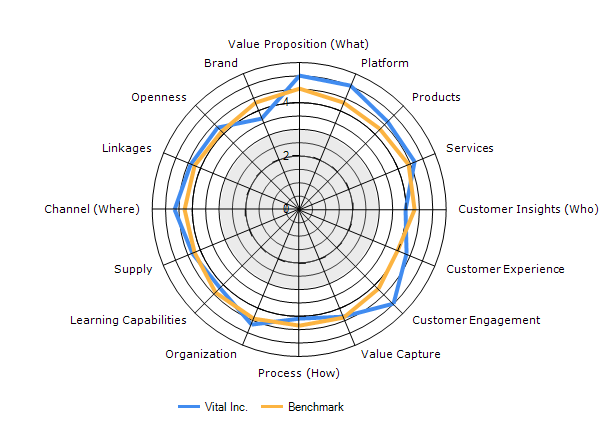

Figure 1: Leadership style with peer benchmark data

• The organization has a fertile field leadership style, a style where the organization tries to use existing capabilities and resources in new ways. Fertile field innovators manage their overall portfolio of core competencies and strategic assets, bringing people together across organizational boundaries to share information and discover opportunities. They create mechanisms that gather, disseminate, and track new ideas and learning for all employees, and determine when and whether to spin off a growing business.

• The organization has a spiral staircase leadership style, where each move builds on prior moves, while focus is kept on an overall goal. Spiral staircase innovators create a profound sense of core purpose, letting everyone know that their innovation contributions are important and giving teams the leadership and autonomy they need to win. Moreover, they create a culture of experimentation and commitment to learning.

• The organization has a cauldron style of leadership, which is an entrepreneurial style where the business model is frequently challenged. Internal markets for new ideas are created, a venture capital model of internal entrepreneurs seeking funding from both internal and approved external sources is encouraged, and peers, rather than bosses, are used to screen and evaluate the opportunities that are stimulated.

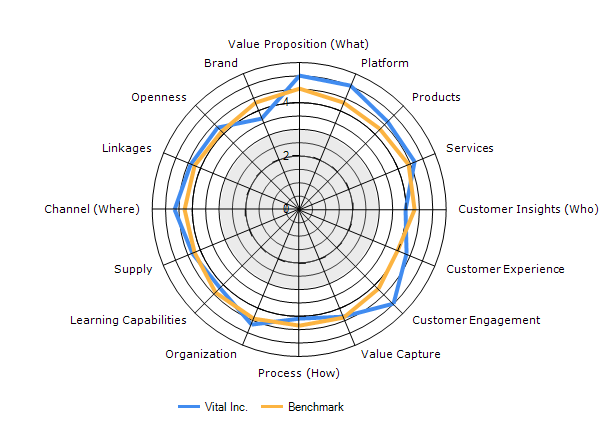

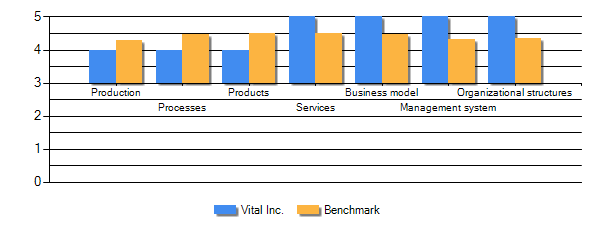

• The organization applies production innovation, meaning the development of new or improved production systems, such as Quality circles, just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing systems and new production planning software for the manufacturing of its products.

• The organization applies process innovation, meaning the development of new or improved processes, e.g. manufacturing processes.

• The organization applies product innovation, meaning the development of new or improved products.

• The organization applies service innovation, meaning the development of new or improved services, e.g, Internet-based services, mobile-based services and embedded services in home electronics and cars.

• The organization applies business model innovation meaning the it develops new or improved business models and value propositions.

• The organization applies management innovation, meaning the development of new or improved management systems such as quality systems, organizational frameworks and performance management systems.

• The organization applies organizational innovation, meaning the development of new or improved organization and communication structures and systems, e.g. a new venture division or a new kind of collaborative platform.

Figure 2: Type of innovation with peer benchmarks.

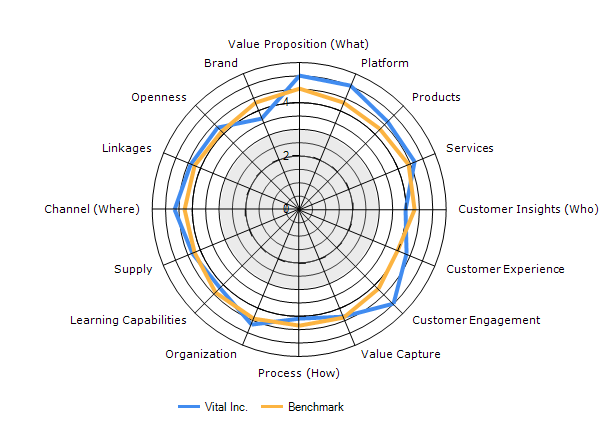

Figure 3: Overall innovation footprint with peer benchmark.

The organization has a strong capability for Value Proposition innovation. Value Propositions describes customers' gain, pain and job to be done. According to Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott and Inigo Arroniz (MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2006, Vo 47, No 3) innovation along this dimension requires the creation of new value propositions that are valued by customers reducing their pain as well as creating a gain — getting their “job done” in a better and smarter way. For example, consider Procter & Gamble's Crest SpinBrush. Introduced in 2001, the product became the world’s bestselling electric toothbrush by 2002. A simple design and the use of disposable AA batteries translated into ease of use, portability and affordability. Moreover, Procter & Gamble’s no-frills approach enabled the SpinBrush to be priced at around $5, substantially cheaper than competing products. Another example is Sony's business model for the Playstation 2 (PS2), one of the three leading game consoles at the time besides the Microsoft Xbox and the Nintendo. It was what Kim and Mauborgne call a red ocean until Nintendo disrupted the industry with the Wii — what Kim and Mauborgne call a blue ocean. Wii introduced casual players and Wii Remote Control, raised the fun factor, and eliminated the cables, hardcore gamers and subsidies (for using advanced technologies). It also reduced the processor speed, the R&D cost and the graphics, making it much simpler.

The organization has a strong capability for platform innovation. A platform is a set of common components, assembly methods or technologies that serve as building blocks for a portfolio of products or services. Platform innovation involves exploiting the “power of commonality” — using modularity to create a diverse set of derivative offerings more quickly and cheaply than if they were stand-alone items. Innovations along this dimension are frequently overlooked even though their power to create value can be considerable. Platform innovation, for example, has allowed Nissan Motor Co. to resurrect its fortunes in the automotive industry (Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott and Inigo Arroniz , MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2006, Vo 47, No 3)

The organization has a strong capability for product innovation. Product innovation is defined as the development of completely new products, making design changes to established products, or the use of new materials or components in the manufacture of established products. The typical objectives of product innovation are the introduction of new products, or enhancing the quality and performance of existing products. Product innovation can be divided into incremental innovation, which aims at improving existing products, partly radical innovation, which aims at developing next generation products, and radical (breakthrough) innovation to explore future product opportunities .

The organization has a strong capability for service innovation. Service innovation can be defined as "a new or considerably changed service concept, client interaction channel, service delivery system or technological concept that individually, but most likely in combination, leads to one or more (re)new(ed) service functions that are new to the firm and that change the service/good offered on the market and require structurally new technological, human or organizational capabilities of the service organization". This definition covers the notions of technological and non-technological innovation. Non-technological innovations in services mainly arise from investment in intangible inputs ( Van Ark et al., 2003).

The organization has a strong capability for customer insights innovation. Customers are the individuals or organizations that use or consume a company’s offerings to satisfy certain needs. To innovate along this dimension, the company can discover new customer segments or uncover unmet (and sometimes unarticulated) needs. Virgin Mobile USA was able to successfully enter the US cellular services market late by focusing on consumers under 30 years old — an underserved segment. To attract that demographic, Virgin offered a compelling value proposition: simplified pricing, no contractual commitments, entertainment features, stylish phones and the irreverence of the Virgin brand. Within three years of its 2002 launch, Virgin had attracted several million subscribers in the highly competitive market (Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott and Inigo Arroniz , MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2006, Vo 47, No 3).

The organization has a strong capability for customer experience innovation. This dimension considers everything a customer sees, hears, feels and otherwise experiences while interacting with an organization at all moments. To innovate here, the organization needs to rethink the interface between the organization and its customers. Consider how the global design firm IDEO, headquartered in Palo Alto, California, has helped health care provider Kaiser Permanente to redesign the customer experience provided to patients. Kaiser has created more comfortable waiting rooms, lobbies with clearer directions and larger exam rooms with space for three or more people and curtains for privacy. Kaiser understands that patients not only need good medical care but also need to have better experiences before, during and after their treatments (Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott and Inigo Arroniz , MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2006, Vo 47, No 3).

The organization has a strong capability for customer engagement innovation. Customer engagement means enabling a consistent, two-way dialogue between you and your customers in order to gain the best possible understanding of your customers' purchasing behavior and the "why's" behind it. Continuously engaging customers is the best way to gain superior customer insights to drive your innovation efforts. There are at least four ways to engage your customers: 1) Get feedback from the most knowledgeable customers. Talk to customers who already know you, your brand and your industry. 2) Ask customers to do small activities - validating and qualifying ideas along the way - is a good approach to getting people's feedback frequently without overwhelming them. 3) Get a longitudinal view of your customers. If you want customers to adapt to new values, skills and vocabularies, it's imperative to have a deep understanding of who they are and how they evolve over time. By grasping how customers evolve over time, you have a better shot at influencing how they might change in the future. 4) Close the feedback loop to the customers to make them feel more appreciated. This will also increase the likelihood that they will continue to participate and contribute. By engaging your customers through tools such as insight communities, you can get back to them and let them know how their input shapes your new product or service. Newsletters or videos posted to your insight community can also help you inform your customers about what impact their participation is having on your decision making.

The organization has a strong capability for value capture innovation. Value capture refers to the mechanism that an organization uses to recapture the value it creates. To innovate along this dimension, the organization can discover untapped revenue streams, develop novel pricing systems and otherwise expand its ability to capture value from interactions with customers and partners. Edmunds.com, the popular automotive website, is a case in point. The company generates revenues from an array of sources, including advertising; licensing of its tools and content to partners like The New York Times and America Online; referrals to insurance, warranty and financing partners; and selling to third parties of data on customer buying behaviour that it collects through its website. These various revenue streams have significantly increased Edmunds’ average sales per visitor (Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott and Inigo Arroniz , MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2006, Vo 47, No 3).

The organization has a strong capability for process innovation. Processes are the configurations of business activities used to conduct internal operations. To innovate along this dimension, an organization can redesign its processes for greater efficiency, higher quality or faster cycle time. Such changes might involve relocating a process or decoupling its front-end from its back-end. That’s the basis of the success of many information technology services firms in India, including companies like Wipro Infotech and Infosys Technologies Ltd. that have created enormous value by perfecting the model of delivering business processes as an outsourced service from a remote location. To accomplish this, each process is decomposed into its constituent elements so that cross-functional teams in multiple countries can perform the work, and the project is coordinated through the use of well-defined protocols. The benefits are flexibility and speed to market, access to a competitive pool of talent (the highly educated and relatively low-cost Indian knowledge worker) and the freedom to redirect resources to core strategic activities (Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott and Inigo Arroniz , MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2006, Vo 47, No 3).

The organization has a strong capability for organizational innovation. Organization is the way in which a company structures itself, its partnerships and its employee roles and responsibilities. Organizational innovation often involves rethinking the scope of the firm’s activities as well as redefining the roles, responsibilities and incentives of different business units and individuals. Thomson Financial, a New York City-based provider of information and technology applications for the financial services industry, transformed its organization by structuring around customer segments instead of products. In this way, Thomson was able to align its operational capabilities and sales organization with customer needs, enabling the company to create offerings like Thomson ONE, an integrated work-flow solution for specific segments of financial services professionals( Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott and Inigo Arroniz , MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2006, Vo 47, No 3).

The organization has strong learning capabilities for innovation. Innovative organizations require a strong learning orientation to gain competitive advantage generating higher profit and/or market shares. Based on in-depth interviews with senior executives and a review of the literature, four components of learning orientation have been identified as critical for driving innovations: 1) commitment to learning, 2) learning from mistakes, 3) open-mindedness, and 4) intra-organizational knowledge sharing.

The organization has a strong capability for supply chain innovation. A supply chain is the sequence of activities and agents that moves goods, services and information from source to delivery of products and services. To innovate in this dimension, an organization can streamline the flow of information through the supply chain, change its structure or enhance the collaboration of its participants. Consider how the apparel retailer Zara in La Coruña, Spain, was able to create a fast and flexible supply chain by making counterintuitive choices in sourcing, design, manufacturing and logistics. Unlike its competitors, Zara does not fully outsource its production. Instead it retains half in-house, allowing it to locate its manufacturing facilities closer to its markets to cut product lead times. Zara eschews economies of scale by making small lots and launching a plethora of designs, allowing it to refresh its designs almost weekly. The organization also ships garments on hangers, a practice that requires more warehouse space but that allows new designs to be displayed more quickly. Thanks to such practices, Zara has decreased the design-to-retail cycle to as short as 15 days and is able to sell most merchandise at full price (Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott and Inigo Arroniz , MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2006, Vo 47, No 3).

The organization has a strong capability for channel innovation. Points of presence are the channels of distribution that a company employs to take offerings to market and the places where its offerings can be bought or used by customers. Innovation in this dimension involves creating new points of presence or using existing ones in creative ways. That’s what Titan Industries Ltd. did when it entered the Indian market with stylish quartz wristwatches in the 1980s. Initially, Titan was locked out of the market because the traditional watch retailing channels were controlled by a competitor. But the company took a fresh look at the industry and asked itself the following fundamental question: Must watches be sold at watch stores? In answering that, Titan found that target customers also shopped at jewellery, appliance and consumer electronics stores. So the company pioneered the concept of selling watches through free-standing kiosks placed within other retail stores. For service and repair, Titan established a nationwide aftersales network through which customers could get their watches fixed. Such innovations have enabled Titan not only to enter the Indian market but also to become the industry leader (Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott and Inigo Arroniz , MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2006, Vo 47, No 3).

The organization has a strong capability for linkage innovation. An organization and its products and services are connected to customers through a network that can sometimes become part of the firm’s competitive advantage. Innovations in this dimension consist of enhancements to the network that increase the value of the organization’s offerings. Consider how Mexican industrial giant CEMEX was able to redefine its offerings in the ready-to-pour concrete business. Traditionally, CEMEX offered a three-hour delivery window for ready-to-pour concrete with a 48-hour advance ordering requirement. But construction is an unpredictable business. Over half of CEMEX’s customers would cancel orders at the last minute, causing logistical problems for the company and financial penalties for those customers. To address this, CEMEX installed an integrated network consisting of GPS systems and computers in its fleet of trucks, a satellite communication system that links each plant and a global Internet portal for tracking the status of orders worldwide. This network now allows CEMEX to offer a 20-minute time window for delivering ready-to-pour concrete, and the company also benefits from better fleet utilisation and lower operating costs (Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott and Inigo Arroniz , MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2006, Vo 47, No 3).

The organization has a strong capability for open innovation. Open innovation, also called external collaboration, is the extension of your innovation organization beyond your organizational boundaries. It includes collaborating with customers, suppliers, rival companies and academic institutions. But is should also include a strategy for the creation, use, and management of intellectual property.

The organization has a weak capability for brand innovation. The brand comprises the symbols, words and/or marks through which the organization communicates its promises to customers. To innovate in this dimension, the company leverages or extends its brand in creative ways. London-based easyGroup has been a leader in this respect. Founded by Stelios Haji-Ioannou, easyGroup owns the “easy” brand and has licensed it to a range of businesses. The core promises of the brand are good value and simplicity, which have now been extended to more than a dozen industries through various offerings such as easyJet, easyCar, easyInternetcafé, easyMoney, easyCinema, easyHotel and easyWatch (Mohanbir Sawhney, Robert C. Wolcott and Inigo Arroniz , MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2006, Vo 47, No 3).

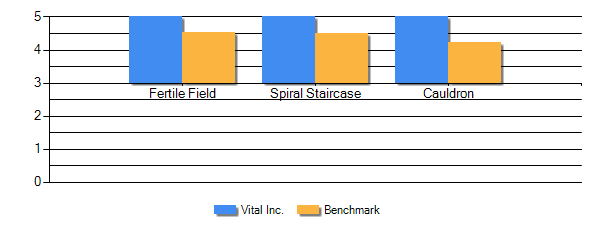

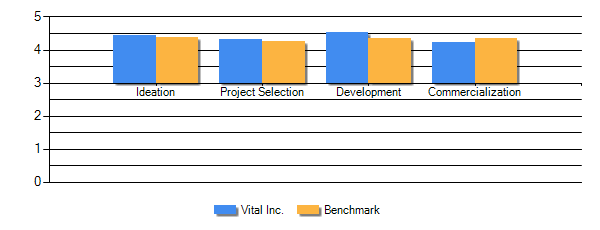

Figure 4: Innovation process with peer benchmark.

The organization has a working ideation phase (in the innovation process). The organization seems to engage suppliers and distributors in the ideation process, bringing independent competitive insights from the marketplace as well as driving open innovation, capturing ideas at any point in the process. The organization also seems to have an understanding of emerging technologies and trends, as well as deep consumer and customer insights and analytics.

The organization has a working project-selection phase (in the innovation process). Strategic decision making and transition plans seem to be in place. The organization seems to be doing technical risk assessments, rigorous decision making around portfolio trade-offs, resource requirements planning, and ongoing assessments of market potential.

The organization has a working development phase (in the innovation process). The organization seems to be doing adequate reverse engineering, supplier-partner engagement in development, design for specific goals, product platform management and engagement with customers to prove real-world feasibility.

The organization has a working commercialization phase (in the innovation process). ). The organization seems to be doing diverse user group management, production ramp-up, regulatory/government relationship management, global enterprise-wide product launch, product lifecycle management and pilot-user selection/controlled rollouts.

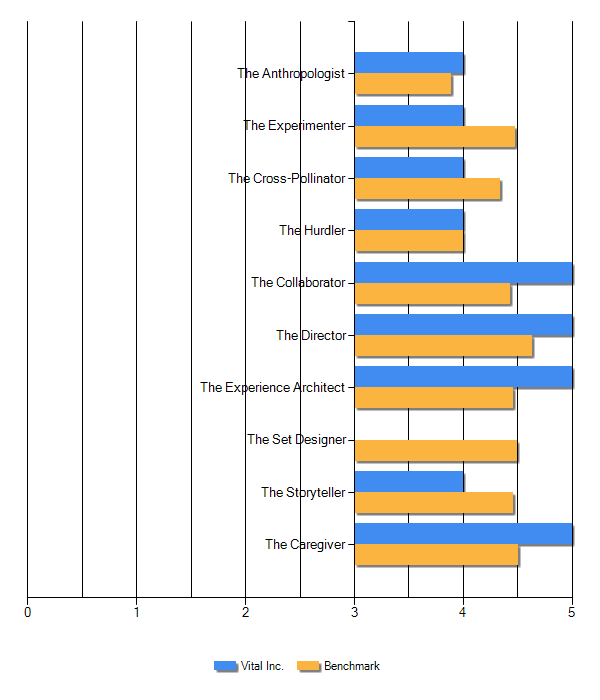

Figure 5: Personas with peer benchmark.

The organization has anthropologists. The anthropologist is rarely stationary but ventures into the field to observe first-hand how people interact with products, services and experiences in order to come up with new innovations. The anthropologist is extremely good at reframing a problem in a new way, humanizing scientific method to apply it to daily life. Anthropologists share such distinguishing characteristics as the wisdom to observe with a truly open mind; empathy; intuition; the ability to "see" things that have gone unnoticed; a tendency to keep running lists of innovative concepts worth emulating and problems that need solving; and a way of seeking inspiration in unusual places.

The organization has experimenters. The experimenter celebrates the process, not the tool, testing and retesting potential scenarios to make ideas tangible. A calculated risk-taker, this person models everything from products to services to proposals in order to efficiently reach solutions. To share the fun of discovery, the experimenter invites others to collaborate, all the while making sure that the entire process is saving time and money.

The organization has cross-pollinators. The cross-pollinator draws associations and connections between seemingly unrelated ideas or concepts to break new ground. Armed with a wide set of interests, an avid curiosity, and an aptitude for learning and teaching, the cross-pollinator brings in big ideas from the outside world to enliven their organization. People in this role can often be identified by their open-mindedness, diligent note-taking, tendency to think in metaphors, and ability to reap inspiration from constraints.

The organization has hurdlers. The hurdler is a tireless problem-solver who who gets a charge out of tackling things that have never been done before. When confronted with a challenge, the hurdler gracefully sidesteps the obstacle while maintaining a quiet, positive determination. This optimism and perseverance can help big ideas to upend the status quo as well as turning setbacks into the organization's greatest successes – despite doomsday forecasting by shortsighted experts.

The organization has collaborators. The collaborator is the rare person who truly values the team over the individual. In the interest of getting things done, the collaborator coaxes people out of their work silos to form multidisciplinary teams. In doing so, the person in this role dissolves traditional boundaries within organizations and creates opportunities for team members to assume new roles. More of a coach than a boss, the collaborator instills their team with the confidence and skills needed to complete the shared journey.

The organization has directors. The director has an acute understanding of the bigger picture, with a firm grasp on the pulse of their organization. Subsequently, the director is talented at setting the stage, targeting opportunities, bringing out the best in their players, and getting things done. Through empowerment and inspiration, the person in this role motivates those around them to take centre stage and embrace the unexpected.

The organization has experience architects. The experience architect is a person who relentlessly focuses on creating remarkable individual experiences. Experience architects facilitate positive encounters with their organization through products, services, digital interactions, spaces, or events. Whether an architect or a sushi chef, the experience architect maps out how to turn something ordinary into something distinctive - even delightful - every chance they get.

The organization lacks set designers. The set designer looks at every day as a chance to liven up their workspace. They promote energetic, inspired cultures by creating work environments that celebrate the individual and stimulate creativity. To keep up with shifting needs and foster continuous innovation, the set designer makes adjustments to a physical space to balance private and collaborative work opportunities. In doing so, this person makes space itself one of the organization's most versatile and powerful tools.

The organisation has storytellers. The storyteller captures our imagination with compelling narratives of initiative, hard work and innovation. This person goes beyond oral tradition to work in whatever medium best fits their skills and message: video, narrative, animation, even comic strips. By rooting their stories in authenticity, the storyteller can spark emotion and action, transmit values and objectives, foster collaboration, create heroes, and lead people and organizations into the future.

The organization has caregivers. The caregiver is the foundation of human-powered innovation. Through empathy, they work to understand each individual customer and to create a relationship. Whether a nurse in a hospital, a salesperson in a retail shop, or a teller at an international financial institution, the caregiver guides the client through the process to provide them with a comfortable, human-centred experience.

This section describes, with diagrams, the company's strengths and weaknesses in relation to explicit strategy, leadership and type of innovation. This has been done by an advanced correlation analysis of innovation capabilities in relation to explicit strategy, leadership and type of innovation. It is useful to understand what the correlations are in the most successful combinations in order to out-compete the competitors.

Capability name | Description | Score | Benchmark |

Systematic Service Innovation | The organization is working systematically to innovate new services that will offer competitive advantage on the market. | 5 ↑ | 4,52 ↑ |

Idea Diffusion | The organization’s structure and/or supporting systems allow you to capture, generate and take advantage of new ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,33 ↑ |

Speed to Market | When the organization decides, it quickly gets new innovations to the market. | 4 ↑ | 4,13 ↑ |

Ramp-Up | The organization lacks the abilty to scale up a launch internationally. | 3 → | 4,24 ↑ |

Idea Generation | The organization systematically looks for new ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,69 ↑ |

A/B Innovation Testing | The organization carries out regular A/B testing of new innovations that systematically compares different variants of the same innovation and studies customer reactions and differences between A and B variants. | 4 ↑ | 3,93 → |

Automated Usage and Experience Analysis | The organization builds in automatic evaluations of how customers use and experience innovations, which it then analyses and evaluates to take the next steps. | 5 ↑ | 4,15 ↑ |

Format Development | The organization studies and analyses other industries' delivery formats as well as innovating its own new ways. | 5 ↑ | 4,25 ↑ |

Channel Development | The organization innovates its distribution channels, e.g. shop-in-shops, pop-up-stores, mobile offices and fast home deliveries. | 4 ↑ | 4,17 ↑ |

Set the stage | The organization does not have staff who create innovative environments, either internally or externally. | 3 → | 4,50 ↑ |

Open Innovation | The organization works regularly with innovation in open environments, i.e. cross border collaboration in all phases of the innovation process, from ideation to commercialization, in order to maximize its innovation performance. | 5 ↑ | 4,33 ↑ |

Innovation Priority | The management prioritises innovation efforts. | 4 ↑ | 4,42 ↑ |

Experiential Customer Insights | The organization evaluates its services through unannounced real customer situations that are logged, analysed and evaluated to result in concrete improvements. | 4 ↑ | 4,42 ↑ |

Prototyping | The organization has a process in place to evaluate and prototype ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,41 ↑ |

Risk Assessment | The organization makes systematic risk assessments. | 5 ↑ | 4,36 ↑ |

DNA Focused | People within the organization discuss and analyse regularly what employees are really good at and what differentiates its customer value proposition, far beyond traditional customer specifications and evaluations. | 5 ↑ | 4,46 ↑ |

R&D Cost Control | The organization is able to drive its innovation projects on or under budget. | 4 ↑ | 4,00 ↑ |

Technology Watch | The organization learns about new technology on a regular basis even if the company does not know how to use it. | 5 ↑ | 4,34 ↑ |

Community Approach | The organization works systematically with open "communities" where customers and others can engage, contribute and learn. | 5 ↑ | 4,30 ↑ |

General Involvement | People, both externally and internally, feel appreciated and involved. | 5 ↑ | 4,43 ↑ |

Social Science | The organization has an anthropological style studying human behavior to gain accurate and new customer insights. | 4 ↑ | 3,89 → |

Design for Reuse | The organization thinks in modules and reuses and further develops other finished parts as complete subsystems for internal or external delivery. | 5 ↑ | 4,28 ↑ |

Service Improvement Tracking | The organization tests new services and compares the outcomes with old services before they are launched. | 5 ↑ | 4,31 ↑ |

Real Need Focus | The organization tries to satisfy its customers' real needs and not what the customers states on a direct question. | 5 ↑ | 4,55 ↑ |

Relationship Building | There are people creating a trustworthy atmosphere building internal and external relationships. | 5 ↑ | 4,51 ↑ |

Cross-Function Collaboration | Collaboration between functions or departments works well and continually generates new ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,37 ↑ |

Supplier Scanning and Involvement | The organization analyzes and innovates all aspects of finding and developing suppliers to the company, and those that deliver to the customer and the customer's customer. | 5 ↑ | 4,30 ↑ |

Clear Vision | Employees are all aware of the company's innovation vision, understand it and work towards it. | 5 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Pricing System | The organization evaluates and adjusts its pricing methodology on a regular basis, based on price testing or other methods. | 5 ↑ | 4,21 ↑ |

Linkages for development | The organization involves external partners, such as universities, in its development. | 5 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Customer Co-Creation | The organization engages its customers in its own development. | 5 ↑ | 4,38 ↑ |

Customers' Behavior Insights | The organization studies and analyses customers' actual behavior in order to segment the market in innovative ways. | 4 ↑ | 4,39 ↑ |

T-Shaped | The organization includes a number of T-shaped people, i.e. those who are broad in their way of thinking and in their education, but capable of acting more deeply in one or two specialist areas. | 4 ↑ | 4,34 ↑ |

External Innovation Engagement | The organization engages its suppliers and partners in the innovation process. | 4 ↑ | 4,49 ↑ |

Innovation Benchmarking | The organization buys and tests innovations from competitors and other industries. | 5 ↑ | 4,07 ↑ |

Product Lifecycle Management | The organization has an effective product lifecycle management system in place. | 5 ↑ | 4,38 ↑ |

Talent Management for Innovation | The organization is constantly looking for new talent that may contribute to its growth and development. | 5 ↑ | 4,62 ↑ |

Understanding of Customers' Decision-Making Processes | The organization has a deep understanding of and insight into customers' decision-making processes. | 4 ↑ | 4,35 ↑ |

Common Platform & Standard Creation | The organization cooperates with external stakeholders including clients to develop platforms such as open source, common markets, common standards, etc. | 5 ↑ | 4,35 ↑ |

Opportunistic | The organization has employees who often take up new opportunities and are encouraged to do so. | 4 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Core Focus | The organization does all kinds of things including non-core work. | 3 → | 4,10 ↑ |

Documented Product Development Process | The organization has a documented process in place to design, develop, test and launch products. | 5 ↑ | 4,36 ↑ |

External Rewards | The organization has a reward system in place for customers to help the organisation in its innovation efforts. | 5 ↑ | 3,93 → |

Knowledge Rewarding | The organization’s employees are rewarded and encouraged to bring in new knowledge. | 4 ↑ | 4,38 ↑ |

Evaluation of Competitors' Products | The organization continually evaluates competitors' products in order to keep ahead of them, learn from them and ultimately beat them. | 5 ↑ | 4,26 ↑ |

Innovation Reward System | There is an internal reward system in place for innovation work. | 5 ↑ | 4,05 ↑ |

Sharing through telling | People within the organization are good at telling about its success and history. | 4 ↑ | 4,46 ↑ |

Demand Generation | The organization creates demand before its innovations are launched. | 4 ↑ | 3,97 → |

Efficient Test Methodology | The organization has a testing methodology in place to find and fix errors as early as possible in the innovation process. | 4 ↑ | 4,44 ↑ |

External Knowledge Sharing | The organization publishes information and insights in order to share and gain knowledge. | 5 ↑ | 4,22 ↑ |

Market Research | The organization undertakes frequent independent market research and assesses the market potential. | 4 ↑ | 4,19 ↑ |

Product to Market | The organization regularly launches new product types to stay ahead of its competitors and to strengthen its customers' loyalty through an innovative approach. | 4 ↑ | 4,23 ↑ |

Consumption Development | The organization is continuously studying and analyzing new consumption patterns on the market. I.e. how end-users consume products and services in reality. | 5 ↑ | 4,44 ↑ |

Patent Exchange | The organization does not exchange technology patents with others in the same or other industries. | 3 → | 3,82 → |

Innovation Measuring | The organization measures and systematically evaluates its innovation efforts. | 4 ↑ | 4,40 ↑ |

Decision Making | The organization has a system to select the projects to be launched. | 4 ↑ | 4,29 ↑ |

Offer Reinforcement | The organization ensures that all customer accounts reinforce what they really offer the market. | 5 ↑ | 4,51 ↑ |

Pilot Testing | The organization tests pilots and learns from them, adapting quickly to the outcomes prior to final launch. | 4 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Evaluative | The organization assigns sufficient time and resources to evaluate projects after they are launched. | 4 ↑ | 4,39 ↑ |

Coaching for Goals | The organization has a goal-oriented leadership model | 5 ↑ | 4,64 ↑ |

Market Regulation Insights | The organization analyses laws, regulations and other external circumstances before deciding to launch an innovation project. | 4 ↑ | 4,53 ↑ |

IP Protection | The organization systematically protects its intellectual property rights. | 4 ↑ | 4,53 ↑ |

Cross-Learning | The organization’s employees learn from each other and from their customers. | 5 ↑ | 4,56 ↑ |

Partner Development | The organization continually scans the market for partners. | 5 ↑ | 4,34 ↑ |

Advantage Visualisation | The organization is adept at clarifying its advantage over competitors. | 4 ↑ | 4,43 ↑ |

Reverse Engineering | The organization does not work with reverse engineering, i.e. buying competitors' products and disassembling them to understand and learn from how they are engineered. | 3 → | 3,83 → |

Table 1: Strengths of capabilities (total of 67) in relation to type of strategy (Incremental or Disruptive).

Capability name | Description | Score | Benchmark |

Market Research | The organization undertakes frequent independent market research and assesses the market potential. | 4 ↑ | 4,19 ↑ |

Systematic Service Innovation | The organization is working systematically to innovate new services that will offer competitive advantage on the market. | 5 ↑ | 4,52 ↑ |

Customers' Behavior Insights | The organization studies and analyses customers' actual behavior in order to segment the market in innovative ways. | 4 ↑ | 4,39 ↑ |

Service Improvement Tracking | The organization tests new services and compares the outcomes with old services before they are launched. | 5 ↑ | 4,31 ↑ |

Understanding of Customers' Decision-Making Processes | The organization has a deep understanding of and insight into customers' decision-making processes. | 4 ↑ | 4,35 ↑ |

Experiential Customer Insights | The organization evaluates its services through unannounced real customer situations that are logged, analysed and evaluated to result in concrete improvements. | 4 ↑ | 4,42 ↑ |

Idea Generation | The organization systematically looks for new ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,69 ↑ |

Innovation Measuring | The organization measures and systematically evaluates its innovation efforts. | 4 ↑ | 4,40 ↑ |

Risk Assessment | The organization makes systematic risk assessments. | 5 ↑ | 4,36 ↑ |

Consumption Development | The organization is continuously studying and analyzing new consumption patterns on the market. I.e. how end-users consume products and services in reality. | 5 ↑ | 4,44 ↑ |

Documented Product Development Process | The organization has a documented process in place to design, develop, test and launch products. | 5 ↑ | 4,36 ↑ |

General Involvement | People, both externally and internally, feel appreciated and involved. | 5 ↑ | 4,43 ↑ |

Offer Reinforcement | The organization ensures that all customer accounts reinforce what they really offer the market. | 5 ↑ | 4,51 ↑ |

Evaluation of Competitors' Products | The organization continually evaluates competitors' products in order to keep ahead of them, learn from them and ultimately beat them. | 5 ↑ | 4,26 ↑ |

Cross-Learning | The organization’s employees learn from each other and from their customers. | 5 ↑ | 4,56 ↑ |

Efficient Test Methodology | The organization has a testing methodology in place to find and fix errors as early as possible in the innovation process. | 4 ↑ | 4,44 ↑ |

Real Need Focus | The organization tries to satisfy its customers' real needs and not what the customers states on a direct question. | 5 ↑ | 4,55 ↑ |

Market Regulation Insights | The organization analyses laws, regulations and other external circumstances before deciding to launch an innovation project. | 4 ↑ | 4,53 ↑ |

Pilot Testing | The organization tests pilots and learns from them, adapting quickly to the outcomes prior to final launch. | 4 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Product Lifecycle Management | The organization has an effective product lifecycle management system in place. | 5 ↑ | 4,38 ↑ |

Pricing System | The organization evaluates and adjusts its pricing methodology on a regular basis, based on price testing or other methods. | 5 ↑ | 4,21 ↑ |

Advantage Visualisation | The organization is adept at clarifying its advantage over competitors. | 4 ↑ | 4,43 ↑ |

Customer Co-Creation | The organization engages its customers in its own development. | 5 ↑ | 4,38 ↑ |

Supplier Scanning and Involvement | The organization analyzes and innovates all aspects of finding and developing suppliers to the company, and those that deliver to the customer and the customer's customer. | 5 ↑ | 4,30 ↑ |

Automated Usage and Experience Analysis | The organization builds in automatic evaluations of how customers use and experience innovations, which it then analyses and evaluates to take the next steps. | 5 ↑ | 4,15 ↑ |

Evaluative | The organization assigns sufficient time and resources to evaluate projects after they are launched. | 4 ↑ | 4,39 ↑ |

Community Approach | The organization works systematically with open "communities" where customers and others can engage, contribute and learn. | 5 ↑ | 4,30 ↑ |

Coaching for Goals | The organization has a goal-oriented leadership model | 5 ↑ | 4,64 ↑ |

DNA Focused | People within the organization discuss and analyse regularly what employees are really good at and what differentiates its customer value proposition, far beyond traditional customer specifications and evaluations. | 5 ↑ | 4,46 ↑ |

Idea Diffusion | The organization’s structure and/or supporting systems allow you to capture, generate and take advantage of new ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,33 ↑ |

Clear Vision | Employees are all aware of the company's innovation vision, understand it and work towards it. | 5 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Demand Generation | The organization creates demand before its innovations are launched. | 4 ↑ | 3,97 → |

Design for Reuse | The organization thinks in modules and reuses and further develops other finished parts as complete subsystems for internal or external delivery. | 5 ↑ | 4,28 ↑ |

Format Development | The organization studies and analyses other industries' delivery formats as well as innovating its own new ways. | 5 ↑ | 4,25 ↑ |

Innovation Priority | The management prioritises innovation efforts. | 4 ↑ | 4,42 ↑ |

Ramp-Up | The organization lacks the abilty to scale up a launch internationally. | 3 → | 4,24 ↑ |

Partner Development | The organization continually scans the market for partners. | 5 ↑ | 4,34 ↑ |

Channel Development | The organization innovates its distribution channels, e.g. shop-in-shops, pop-up-stores, mobile offices and fast home deliveries. | 4 ↑ | 4,17 ↑ |

Product to Market | The organization regularly launches new product types to stay ahead of its competitors and to strengthen its customers' loyalty through an innovative approach. | 4 ↑ | 4,23 ↑ |

Talent Management for Innovation | The organization is constantly looking for new talent that may contribute to its growth and development. | 5 ↑ | 4,62 ↑ |

External Innovation Engagement | The organization engages its suppliers and partners in the innovation process. | 4 ↑ | 4,49 ↑ |

Sharing through telling | People within the organization are good at telling about its success and history. | 4 ↑ | 4,46 ↑ |

Prototyping | The organization has a process in place to evaluate and prototype ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,41 ↑ |

Speed to Market | When the organization decides, it quickly gets new innovations to the market. | 4 ↑ | 4,13 ↑ |

Relationship Building | There are people creating a trustworthy atmosphere building internal and external relationships. | 5 ↑ | 4,51 ↑ |

Cross-Function Collaboration | Collaboration between functions or departments works well and continually generates new ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,37 ↑ |

A/B Innovation Testing | The organization carries out regular A/B testing of new innovations that systematically compares different variants of the same innovation and studies customer reactions and differences between A and B variants. | 4 ↑ | 3,93 → |

External Rewards | The organization has a reward system in place for customers to help the organisation in its innovation efforts. | 5 ↑ | 3,93 → |

Knowledge Rewarding | The organization’s employees are rewarded and encouraged to bring in new knowledge. | 4 ↑ | 4,38 ↑ |

Common Platform & Standard Creation | The organization cooperates with external stakeholders including clients to develop platforms such as open source, common markets, common standards, etc. | 5 ↑ | 4,35 ↑ |

Set the stage | The organization does not have staff who create innovative environments, either internally or externally. | 3 → | 4,50 ↑ |

T-Shaped | The organization includes a number of T-shaped people, i.e. those who are broad in their way of thinking and in their education, but capable of acting more deeply in one or two specialist areas. | 4 ↑ | 4,34 ↑ |

Opportunistic | The organization has employees who often take up new opportunities and are encouraged to do so. | 4 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

R&D Cost Control | The organization is able to drive its innovation projects on or under budget. | 4 ↑ | 4,00 ↑ |

IP Protection | The organization systematically protects its intellectual property rights. | 4 ↑ | 4,53 ↑ |

Decision Making | The organization has a system to select the projects to be launched. | 4 ↑ | 4,29 ↑ |

Innovation Reward System | There is an internal reward system in place for innovation work. | 5 ↑ | 4,05 ↑ |

Social Science | The organization has an anthropological style studying human behavior to gain accurate and new customer insights. | 4 ↑ | 3,89 → |

Innovation Benchmarking | The organization buys and tests innovations from competitors and other industries. | 5 ↑ | 4,07 ↑ |

External Knowledge Sharing | The organization publishes information and insights in order to share and gain knowledge. | 5 ↑ | 4,22 ↑ |

Open Innovation | The organization works regularly with innovation in open environments, i.e. cross border collaboration in all phases of the innovation process, from ideation to commercialization, in order to maximize its innovation performance. | 5 ↑ | 4,33 ↑ |

Linkages for development | The organization involves external partners, such as universities, in its development. | 5 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Core Focus | The organization does all kinds of things including non-core work. | 3 → | 4,10 ↑ |

Technology Watch | The organization learns about new technology on a regular basis even if the company does not know how to use it. | 5 ↑ | 4,34 ↑ |

Patent Exchange | The organization does not exchange technology patents with others in the same or other industries. | 3 → | 3,82 → |

Reverse Engineering | The organization does not work with reverse engineering, i.e. buying competitors' products and disassembling them to understand and learn from how they are engineered. | 3 → | 3,83 → |

Table 2: Strengths of capabilities (total of 67) in relation to the strategic direction of the innovation work.

Capability name | Description | Score | Benchmark |

Systematic Service Innovation | The organization is working systematically to innovate new services that will offer competitive advantage on the market. | 5 ↑ | 4,52 ↑ |

Common Platform & Standard Creation | The organization cooperates with external stakeholders including clients to develop platforms such as open source, common markets, common standards, etc. | 5 ↑ | 4,35 ↑ |

Idea Diffusion | The organization’s structure and/or supporting systems allow you to capture, generate and take advantage of new ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,33 ↑ |

Product to Market | The organization regularly launches new product types to stay ahead of its competitors and to strengthen its customers' loyalty through an innovative approach. | 4 ↑ | 4,23 ↑ |

Customer Co-Creation | The organization engages its customers in its own development. | 5 ↑ | 4,38 ↑ |

Cross-Function Collaboration | Collaboration between functions or departments works well and continually generates new ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,37 ↑ |

Clear Vision | Employees are all aware of the company's innovation vision, understand it and work towards it. | 5 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Innovation Priority | The management prioritises innovation efforts. | 4 ↑ | 4,42 ↑ |

Speed to Market | When the organization decides, it quickly gets new innovations to the market. | 4 ↑ | 4,13 ↑ |

Service Improvement Tracking | The organization tests new services and compares the outcomes with old services before they are launched. | 5 ↑ | 4,31 ↑ |

Idea Generation | The organization systematically looks for new ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,69 ↑ |

Experiential Customer Insights | The organization evaluates its services through unannounced real customer situations that are logged, analysed and evaluated to result in concrete improvements. | 4 ↑ | 4,42 ↑ |

Design for Reuse | The organization thinks in modules and reuses and further develops other finished parts as complete subsystems for internal or external delivery. | 5 ↑ | 4,28 ↑ |

Partner Development | The organization continually scans the market for partners. | 5 ↑ | 4,34 ↑ |

Advantage Visualisation | The organization is adept at clarifying its advantage over competitors. | 4 ↑ | 4,43 ↑ |

Pricing System | The organization evaluates and adjusts its pricing methodology on a regular basis, based on price testing or other methods. | 5 ↑ | 4,21 ↑ |

General Involvement | People, both externally and internally, feel appreciated and involved. | 5 ↑ | 4,43 ↑ |

Real Need Focus | The organization tries to satisfy its customers' real needs and not what the customers states on a direct question. | 5 ↑ | 4,55 ↑ |

Understanding of Customers' Decision-Making Processes | The organization has a deep understanding of and insight into customers' decision-making processes. | 4 ↑ | 4,35 ↑ |

Supplier Scanning and Involvement | The organization analyzes and innovates all aspects of finding and developing suppliers to the company, and those that deliver to the customer and the customer's customer. | 5 ↑ | 4,30 ↑ |

Customers' Behavior Insights | The organization studies and analyses customers' actual behavior in order to segment the market in innovative ways. | 4 ↑ | 4,39 ↑ |

Coaching for Goals | The organization has a goal-oriented leadership model | 5 ↑ | 4,64 ↑ |

Evaluation of Competitors' Products | The organization continually evaluates competitors' products in order to keep ahead of them, learn from them and ultimately beat them. | 5 ↑ | 4,26 ↑ |

Consumption Development | The organization is continuously studying and analyzing new consumption patterns on the market. I.e. how end-users consume products and services in reality. | 5 ↑ | 4,44 ↑ |

External Innovation Engagement | The organization engages its suppliers and partners in the innovation process. | 4 ↑ | 4,49 ↑ |

Documented Product Development Process | The organization has a documented process in place to design, develop, test and launch products. | 5 ↑ | 4,36 ↑ |

Community Approach | The organization works systematically with open "communities" where customers and others can engage, contribute and learn. | 5 ↑ | 4,30 ↑ |

Offer Reinforcement | The organization ensures that all customer accounts reinforce what they really offer the market. | 5 ↑ | 4,51 ↑ |

Open Innovation | The organization works regularly with innovation in open environments, i.e. cross border collaboration in all phases of the innovation process, from ideation to commercialization, in order to maximize its innovation performance. | 5 ↑ | 4,33 ↑ |

Automated Usage and Experience Analysis | The organization builds in automatic evaluations of how customers use and experience innovations, which it then analyses and evaluates to take the next steps. | 5 ↑ | 4,15 ↑ |

Pilot Testing | The organization tests pilots and learns from them, adapting quickly to the outcomes prior to final launch. | 4 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

DNA Focused | People within the organization discuss and analyse regularly what employees are really good at and what differentiates its customer value proposition, far beyond traditional customer specifications and evaluations. | 5 ↑ | 4,46 ↑ |

External Knowledge Sharing | The organization publishes information and insights in order to share and gain knowledge. | 5 ↑ | 4,22 ↑ |

A/B Innovation Testing | The organization carries out regular A/B testing of new innovations that systematically compares different variants of the same innovation and studies customer reactions and differences between A and B variants. | 4 ↑ | 3,93 → |

External Rewards | The organization has a reward system in place for customers to help the organisation in its innovation efforts. | 5 ↑ | 3,93 → |

Core Focus | The organization does all kinds of things including non-core work. | 3 → | 4,10 ↑ |

R&D Cost Control | The organization is able to drive its innovation projects on or under budget. | 4 ↑ | 4,00 ↑ |

Technology Watch | The organization learns about new technology on a regular basis even if the company does not know how to use it. | 5 ↑ | 4,34 ↑ |

Opportunistic | The organization has employees who often take up new opportunities and are encouraged to do so. | 4 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Relationship Building | There are people creating a trustworthy atmosphere building internal and external relationships. | 5 ↑ | 4,51 ↑ |

Ramp-Up | The organization lacks the abilty to scale up a launch internationally. | 3 → | 4,24 ↑ |

Format Development | The organization studies and analyses other industries' delivery formats as well as innovating its own new ways. | 5 ↑ | 4,25 ↑ |

Linkages for development | The organization involves external partners, such as universities, in its development. | 5 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Risk Assessment | The organization makes systematic risk assessments. | 5 ↑ | 4,36 ↑ |

Market Research | The organization undertakes frequent independent market research and assesses the market potential. | 4 ↑ | 4,19 ↑ |

Knowledge Rewarding | The organization’s employees are rewarded and encouraged to bring in new knowledge. | 4 ↑ | 4,38 ↑ |

Channel Development | The organization innovates its distribution channels, e.g. shop-in-shops, pop-up-stores, mobile offices and fast home deliveries. | 4 ↑ | 4,17 ↑ |

Cross-Learning | The organization’s employees learn from each other and from their customers. | 5 ↑ | 4,56 ↑ |

Prototyping | The organization has a process in place to evaluate and prototype ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,41 ↑ |

Evaluative | The organization assigns sufficient time and resources to evaluate projects after they are launched. | 4 ↑ | 4,39 ↑ |

Efficient Test Methodology | The organization has a testing methodology in place to find and fix errors as early as possible in the innovation process. | 4 ↑ | 4,44 ↑ |

Talent Management for Innovation | The organization is constantly looking for new talent that may contribute to its growth and development. | 5 ↑ | 4,62 ↑ |

Innovation Measuring | The organization measures and systematically evaluates its innovation efforts. | 4 ↑ | 4,40 ↑ |

Demand Generation | The organization creates demand before its innovations are launched. | 4 ↑ | 3,97 → |

Set the stage | The organization does not have staff who create innovative environments, either internally or externally. | 3 → | 4,50 ↑ |

Sharing through telling | People within the organization are good at telling about its success and history. | 4 ↑ | 4,46 ↑ |

T-Shaped | The organization includes a number of T-shaped people, i.e. those who are broad in their way of thinking and in their education, but capable of acting more deeply in one or two specialist areas. | 4 ↑ | 4,34 ↑ |

Innovation Reward System | There is an internal reward system in place for innovation work. | 5 ↑ | 4,05 ↑ |

Market Regulation Insights | The organization analyses laws, regulations and other external circumstances before deciding to launch an innovation project. | 4 ↑ | 4,53 ↑ |

Innovation Benchmarking | The organization buys and tests innovations from competitors and other industries. | 5 ↑ | 4,07 ↑ |

Social Science | The organization has an anthropological style studying human behavior to gain accurate and new customer insights. | 4 ↑ | 3,89 → |

Decision Making | The organization has a system to select the projects to be launched. | 4 ↑ | 4,29 ↑ |

Product Lifecycle Management | The organization has an effective product lifecycle management system in place. | 5 ↑ | 4,38 ↑ |

IP Protection | The organization systematically protects its intellectual property rights. | 4 ↑ | 4,53 ↑ |

Patent Exchange | The organization does not exchange technology patents with others in the same or other industries. | 3 → | 3,82 → |

Reverse Engineering | The organization does not work with reverse engineering, i.e. buying competitors' products and disassembling them to understand and learn from how they are engineered. | 3 → | 3,83 → |

Table 3: Strengths of capabilities (total of 67) in relation to leadership style.

Capability name | Description | Score | Benchmark |

Product to Market | The organization regularly launches new product types to stay ahead of its competitors and to strengthen its customers' loyalty through an innovative approach. | 4 ↑ | 4,23 ↑ |

Systematic Service Innovation | The organization is working systematically to innovate new services that will offer competitive advantage on the market. | 5 ↑ | 4,52 ↑ |

Idea Generation | The organization systematically looks for new ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,69 ↑ |

Documented Product Development Process | The organization has a documented process in place to design, develop, test and launch products. | 5 ↑ | 4,36 ↑ |

Product Lifecycle Management | The organization has an effective product lifecycle management system in place. | 5 ↑ | 4,38 ↑ |

Pilot Testing | The organization tests pilots and learns from them, adapting quickly to the outcomes prior to final launch. | 4 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Evaluation of Competitors' Products | The organization continually evaluates competitors' products in order to keep ahead of them, learn from them and ultimately beat them. | 5 ↑ | 4,26 ↑ |

Talent Management for Innovation | The organization is constantly looking for new talent that may contribute to its growth and development. | 5 ↑ | 4,62 ↑ |

Design for Reuse | The organization thinks in modules and reuses and further develops other finished parts as complete subsystems for internal or external delivery. | 5 ↑ | 4,28 ↑ |

Advantage Visualisation | The organization is adept at clarifying its advantage over competitors. | 4 ↑ | 4,43 ↑ |

Efficient Test Methodology | The organization has a testing methodology in place to find and fix errors as early as possible in the innovation process. | 4 ↑ | 4,44 ↑ |

External Innovation Engagement | The organization engages its suppliers and partners in the innovation process. | 4 ↑ | 4,49 ↑ |

Real Need Focus | The organization tries to satisfy its customers' real needs and not what the customers states on a direct question. | 5 ↑ | 4,55 ↑ |

Experiential Customer Insights | The organization evaluates its services through unannounced real customer situations that are logged, analysed and evaluated to result in concrete improvements. | 4 ↑ | 4,42 ↑ |

Clear Vision | Employees are all aware of the company's innovation vision, understand it and work towards it. | 5 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Innovation Priority | The management prioritises innovation efforts. | 4 ↑ | 4,42 ↑ |

Cross-Learning | The organization’s employees learn from each other and from their customers. | 5 ↑ | 4,56 ↑ |

Customers' Behavior Insights | The organization studies and analyses customers' actual behavior in order to segment the market in innovative ways. | 4 ↑ | 4,39 ↑ |

Idea Diffusion | The organization’s structure and/or supporting systems allow you to capture, generate and take advantage of new ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,33 ↑ |

Prototyping | The organization has a process in place to evaluate and prototype ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,41 ↑ |

Offer Reinforcement | The organization ensures that all customer accounts reinforce what they really offer the market. | 5 ↑ | 4,51 ↑ |

IP Protection | The organization systematically protects its intellectual property rights. | 4 ↑ | 4,53 ↑ |

Linkages for development | The organization involves external partners, such as universities, in its development. | 5 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Knowledge Rewarding | The organization’s employees are rewarded and encouraged to bring in new knowledge. | 4 ↑ | 4,38 ↑ |

Coaching for Goals | The organization has a goal-oriented leadership model | 5 ↑ | 4,64 ↑ |

Opportunistic | The organization has employees who often take up new opportunities and are encouraged to do so. | 4 ↑ | 4,48 ↑ |

Relationship Building | There are people creating a trustworthy atmosphere building internal and external relationships. | 5 ↑ | 4,51 ↑ |

Service Improvement Tracking | The organization tests new services and compares the outcomes with old services before they are launched. | 5 ↑ | 4,31 ↑ |

Decision Making | The organization has a system to select the projects to be launched. | 4 ↑ | 4,29 ↑ |

Partner Development | The organization continually scans the market for partners. | 5 ↑ | 4,34 ↑ |

Consumption Development | The organization is continuously studying and analyzing new consumption patterns on the market. I.e. how end-users consume products and services in reality. | 5 ↑ | 4,44 ↑ |

General Involvement | People, both externally and internally, feel appreciated and involved. | 5 ↑ | 4,43 ↑ |

Market Regulation Insights | The organization analyses laws, regulations and other external circumstances before deciding to launch an innovation project. | 4 ↑ | 4,53 ↑ |

Ramp-Up | The organization lacks the abilty to scale up a launch internationally. | 3 → | 4,24 ↑ |

Customer Co-Creation | The organization engages its customers in its own development. | 5 ↑ | 4,38 ↑ |

Innovation Measuring | The organization measures and systematically evaluates its innovation efforts. | 4 ↑ | 4,40 ↑ |

Set the stage | The organization does not have staff who create innovative environments, either internally or externally. | 3 → | 4,50 ↑ |

Supplier Scanning and Involvement | The organization analyzes and innovates all aspects of finding and developing suppliers to the company, and those that deliver to the customer and the customer's customer. | 5 ↑ | 4,30 ↑ |

Speed to Market | When the organization decides, it quickly gets new innovations to the market. | 4 ↑ | 4,13 ↑ |

Cross-Function Collaboration | Collaboration between functions or departments works well and continually generates new ideas. | 4 ↑ | 4,37 ↑ |

Common Platform & Standard Creation | The organization cooperates with external stakeholders including clients to develop platforms such as open source, common markets, common standards, etc. | 5 ↑ | 4,35 ↑ |

Evaluative | The organization assigns sufficient time and resources to evaluate projects after they are launched. | 4 ↑ | 4,39 ↑ |

Open Innovation | The organization works regularly with innovation in open environments, i.e. cross border collaboration in all phases of the innovation process, from ideation to commercialization, in order to maximize its innovation performance. | 5 ↑ | 4,33 ↑ |

Risk Assessment | The organization makes systematic risk assessments. | 5 ↑ | 4,36 ↑ |

Community Approach | The organization works systematically with open "communities" where customers and others can engage, contribute and learn. | 5 ↑ | 4,30 ↑ |

T-Shaped | The organization includes a number of T-shaped people, i.e. those who are broad in their way of thinking and in their education, but capable of acting more deeply in one or two specialist areas. | 4 ↑ | 4,34 ↑ |

DNA Focused | People within the organization discuss and analyse regularly what employees are really good at and what differentiates its customer value proposition, far beyond traditional customer specifications and evaluations. | 5 ↑ | 4,46 ↑ |

Sharing through telling | People within the organization are good at telling about its success and history. | 4 ↑ | 4,46 ↑ |

R&D Cost Control | The organization is able to drive its innovation projects on or under budget. | 4 ↑ | 4,00 ↑ |

Pricing System | The organization evaluates and adjusts its pricing methodology on a regular basis, based on price testing or other methods. | 5 ↑ | 4,21 ↑ |

Technology Watch | The organization learns about new technology on a regular basis even if the company does not know how to use it. | 5 ↑ | 4,34 ↑ |

Channel Development | The organization innovates its distribution channels, e.g. shop-in-shops, pop-up-stores, mobile offices and fast home deliveries. | 4 ↑ | 4,17 ↑ |

Understanding of Customers' Decision-Making Processes | The organization has a deep understanding of and insight into customers' decision-making processes. | 4 ↑ | 4,35 ↑ |

Market Research | The organization undertakes frequent independent market research and assesses the market potential. | 4 ↑ | 4,19 ↑ |

Innovation Reward System | There is an internal reward system in place for innovation work. | 5 ↑ | 4,05 ↑ |

A/B Innovation Testing | The organization carries out regular A/B testing of new innovations that systematically compares different variants of the same innovation and studies customer reactions and differences between A and B variants. | 4 ↑ | 3,93 → |

Automated Usage and Experience Analysis | The organization builds in automatic evaluations of how customers use and experience innovations, which it then analyses and evaluates to take the next steps. | 5 ↑ | 4,15 ↑ |

Innovation Benchmarking | The organization buys and tests innovations from competitors and other industries. | 5 ↑ | 4,07 ↑ |

Demand Generation | The organization creates demand before its innovations are launched. | 4 ↑ | 3,97 → |

Format Development | The organization studies and analyses other industries' delivery formats as well as innovating its own new ways. | 5 ↑ | 4,25 ↑ |

Core Focus | The organization does all kinds of things including non-core work. | 3 → | 4,10 ↑ |

External Knowledge Sharing | The organization publishes information and insights in order to share and gain knowledge. | 5 ↑ | 4,22 ↑ |

Reverse Engineering | The organization does not work with reverse engineering, i.e. buying competitors' products and disassembling them to understand and learn from how they are engineered. | 3 → | 3,83 → |

Social Science | The organization has an anthropological style studying human behavior to gain accurate and new customer insights. | 4 ↑ | 3,89 → |

External Rewards | The organization has a reward system in place for customers to help the organisation in its innovation efforts. | 5 ↑ | 3,93 → |

Patent Exchange | The organization does not exchange technology patents with others in the same or other industries. | 3 → | 3,82 → |

Table 4: Strengths of capabilities (total of 67) in relation to type of innovation.

This section has 5 recommendations, each of them numbered in accordance to a specific part of Innovation 360's Innovation Framework.

Establish an international launch process.

Engage set designers within the company that create physical spaces that enable both private and collaborative work and that makes space itself one of the organisation’s most versatile and powerful tools.

Identify non-core process suitable for outsourcing, find suitable suppliers and start outsourcing those processes to them.

Set up an inhouse process and facility for doing frequent product teardowns, i.e. disassembling competitor's products to understand and learn from how they are engineered.

If appropriate, start exchanging technology patents that can be used for innovation by you, or other organisations in the same or other industries.

The InnoSurvey™ innovation capability measurement, as presented in this report, is based on a combination of our underlying innovation framework and our large innovation database. The innovation framework is defined by five strategic questions (see figure 1), and it is based on decades of research and practices and therefore a very powerful tool and foundation for InnoSurvey™ . Here is a brief introduction to the InnoSurvey™ innovation framework:

Figure 6: The Innovation 360 Group´s innovation Framework (Source: Penker, 2011)

The simple question: Why Innovate? lead us to examine the strategic nature of innovation. We know that innovation is a strategic necessity, because the purpose of innovation is to ensure that your organisation survives, and the evidence overwhelmingly shows that any organisation that doesn’t innovate probably won’t stay in business for long. Hence, your innovation process should be aligned with your organisation’s strategy, and innovation should be a key actor that defines how your strategy will be realised. This is an essential cornerstone of the innovation framework.

When we ask the question: What to innovate? We recognise that the unpredictable nature of change requires us to prepare for many types of innovation options for a wide range of possible futures. Therefore we define seven different types of innovation in our framework, and they are all equally important and relevant aspects of our innovation capability measurements.

The answer to this question is that a rigorous innovation process is essential. The process must be driven by strategic intent, the “why” of innovation, so in fact the innovation process itself begins with strategy. The second step is the “what” of innovation; this is a highly strategic question and not just a happening. Many organisations believe this is one of the first steps, but in reality it is in the middle of a strategic, well-implemented innovation process. The framework is based on the conception that a rigorous innovation process is necessary in order to be a world-class innovator, and the framework therefore stipulates that there can be five different styles, ten different roles, 67 capabilities and four different process steps to consider in a well defined, rigorous innovation process.

We have seen that while everyone participates in a robust innovation culture, there are three distinct roles to be played in achieving broad and consistent innovation results; The Innovation Director, The Innovation Ideator and The Innovation Champions. However, these roles must be in harmony with the personalities (personas) of those participating in the innovation work.

An Innovation process is realized by; the tools and infrastructures that support it and the people involved in the innovation process, be they internal and/or external to the company or organization. There are four elements to consider relating to innovation infrastructure; these are:

· The type of innovation, e.g. open innovation, engaging people internally and externally.

· Collaborative platforms to support agile and fast value creation.

· The physical work place, where people are engaged and motivated.

· Methods to support and encourage the innovation process.

The simple answer to the “When” question is all the time! However, everything needs to be measured to fully understand its impact, especially creative work such as innovation. It is imperative to really understand what is driving value and to measure the work effort and the end results, in order to optimise the outcome of the innovation work. In the innovation framework we therefore assume that innovation will take place constantly and at high pace and that it will be guided and monitored by metrics and coached for value and results.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica (1974) an innovation is the introduction of new technologies, held by some writers to be a primary factor in economic growth, which is the core of my research question. Innovations are driven by opportunities and capabilities. Drucker (1998) pointed out four areas of opportunity that exist within a company: unexpected occurrences, incongruities, process needs and industry and market changes.

Outside the company, there are three additional sources of opportunity: demographic changes, changes in perception and new knowledge. It is also possible to consider the linkage to other organisations as an asset in itself. Tovstiga and Birchall (2005) argue that firms are nodes in lager networks that create value by transforming opportunities into businesses by strategic deployment of capabilities.

Moreover, they argue that firms are continuously looking for opportunities within the environment, turning them into a competitive advantage through transformation innovation, and ultimately gaining profitable growth. To summarise, innovation can be seen from two perspectives: from the internal perspective of a firm’s capabilities, and from the external market perspective where the performance can be measured and success judged (Tovstiga & Birchall, 2005).

Companies can be categorised into three types according to the kind of innovation strategy that they adopt: need seekers, market readers and technology drivers. The need seekers look for potential opportunities by applying superior understanding of the market and rapid go-to-markets, market readers capitalise on existing trends and understanding of markets, while technology drivers drive for breakthrough innovations based on new technology (Jaruzelski & Dehoff, 2010). New reports based on more than ten years of measurements show that need seekers who have aligned their strategies with their capabilities are the most successful in generating return on investments in R&D (Jaruzelski, Staack, & Goehle, 2014).

In current thinking, there are several types of innovations that are discussed, as well as what is called strategic innovation and innovation of business models. Another trend, known as open innovation, is where innovations are driven in symbiosis with external parties. Many practitioners, as well as academics, emphasise the importance of building the right capabilities and adopting the right leadership style, as well as understanding and developing corporate culture in a way that maximises the value of innovation work.